The 1983 Hollywood comedy, Trading Places, offered many laymen their first glimpse at the hustle-and-bustle world of commodities trading. The film features a pair of imperious billionaire brothers, the Dukes, who attempt to add to their fortune by illegally manipulating the price of orange juice in the futures market.

The 1983 Hollywood comedy, Trading Places, offered many laymen their first glimpse at the hustle-and-bustle world of commodities trading. The film features a pair of imperious billionaire brothers, the Dukes, who attempt to add to their fortune by illegally manipulating the price of orange juice in the futures market.

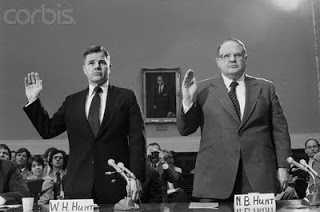

The protagonists, played by Dan Akroyd and Eddie Murphy, foil the brothers’ plot and leave the Dukes disgraced and penniless. But although the movie was a work of fiction, the Duke characters were in fact based on a pair of real-life brothers—Bunker and Herbert Hunt—and their story is truly stranger than fiction.

H.L. Hunt and Heirs

He Hunt Brothers’ story begins with their father, H.L. Hunt, who, when he died in 1974, was the richest man in America. But despite his sons’ affinity for the precious metal, H.L. Hunt was not born with a silver spoon in his mouth. To the contrary, H.L. left home at sixteen and worked as a dishwasher, a mule-team driver, a logger, a farmhand, and a construction worker, before finally finding his true calling—poker.

By age thirty-six, poker had made H.L. Hunt a small fortune, which he rolled into his next investment—Florida real estate. After profiting from that boom, Hunt took the proceeds and began drilling for oil. This is how he became the world’s richest man—always taking bigger and bolder risks, and routinely coming out on top — at least in his business life. On the personal front, H.L. had a little more than he could handle.

He had one wife in Texas and another in Florida—at the same time, and separate families in both states. When his first wife died, he took a third wife with whom he had already had four children. All in all, he had fifteen sons and daughters, many of who went on to become moguls in their own right. Bunker and Herbert were chief among them.

From Failure to Extreme Wealth

Nelson Bunker Hunt (who went by “Bunker”) was born in 1926, the second-eldest son of H.L. and his first wife, Lyda. Their eldest son, Hassie, had a mental condition that ultimately led to a full-frontal lobotomy, but prior to that, Hassie had struck out on his own in the oil business, amassing a considerable fortune before his twenty-fifth birthday.

With Hassie incapacitated, Bunker was the heir apparent to his father’s fortune. He owned and operated Penrod Drilling Company with his brothers William Herbert (who, like his brother Nelson Bunker, also went by his middle name) and Lamar, and Placid Oil Company with five of his siblings. But Bunker would gain the most notoriety—and wealth—for his individual efforts in business.

Initially, Bunker’s own ventures were not very successful. He lost $11 million drilling in dry holes in Pakistan, and after leasing two tracts in Libya, he eventually had to sell a 50% stake in one of them in order to meet cash-flow demands. By twist of fate, that tract held the largest oilfield yet discovered in Africa, and in 1961, Bunker surpassed his own father to become the richest man in the world (excluding monarchs and despots).

Bunker’s Attraction to Silver

In what is widely characterized as one of the most draconian acts in the history of the United States government, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 6102, “The Gold Confiscation Act,” on April 5, 1933. For the next forty-one years, it was illegal for U.S. citizens to “hoard” gold. With gold, the traditional store of wealth, out of the question, Bunker Hunt decided to hold his oil profits in silver.

The early 1970s were a prosperous time for Bunker. His Libyan oil leases were producing $30 million a year, even as oil was priced at just $3 per barrel. But nevertheless, Bunker did not like what he saw when he surveyed the global economic landscape. Years of post-New Deal Keynesianism was starting to catch up with the U.S., and inflation was gaining steam. The war in Vietnam was unpopular, and people were rioting in the streets.

Confidence in the federal government was at an all-time low, and the Middle East—where Bunker held so much of his wealth—was extremely volatile.

Silver was just $1.50 an ounce when Bunker and his brother Herbert began buying it in 1970. Over the course of the next three years, the brothers purchased approximately 200,000 ounces of the precious metal, and saw it double in price to $3 per ounce.

Then in 1973, Moammar al-Qaddafi nationalized Bunker’s oil fields and demanded a 51% royalty. Understandably, Bunker was furious. He was incensed that the State Department didn’t do more to defend his property, and he was also angry at the major U.S. oil companies for not taking a tougher stand against Qaddafi.

He blamed his long-time rivals, the Rockefellers, whom he considered to be pseudo-socialists, for the loss of his Libyan oil filed, and Bunker firmly believed that the U.S. was on the road to serfdom. As a hedge against what he saw as the inevitable, Bunker ramped up his silver buying.

Bunker Hunt’s Silver Mania: 1974 to 1980

By 1974, Bunker and Herbert had accumulated futures contracts for approximately fifty-five million ounces of silver—8% of the global supply at that time.

By 1974, Bunker and Herbert had accumulated futures contracts for approximately fifty-five million ounces of silver—8% of the global supply at that time.

But rather than selling the contracts to turn a profit, as most commodity traders do, the Hunt brothers had every intention of taking delivery of their silver—and they didn’t intend to keep it in the U.S. either.

The conservative Hunts, who were members of the John Birch Society, believed another government confiscation was on the horizon, and since the feds had already taken gold, silver would be next. Thus, Bunker and Herbert chartered three 707 jets from Texas to Chicago and New York—in the dead of night—and loaded them with forty million ounces of silver to be whisked away to Switzerland for safe keeping. The remaining fifteen million ounces stayed in the U.S., but the Hunts would assume no greater risk.

By that spring, silver doubled again to $6 per ounce. Rumors abounded that the brothers were attempting to corner the market, thus sending prices higher. The Hunts met with the Shah of Iran and the King of Saudi Arabia, and although the Shah snubbed them and the King was eventually assassinated, the Hunts eventually began working with a Saudi sheik who was thought to represent his nation’s royal family. By 1976, the brothers had accumulated another twenty million ounces of silver, and by ’79, the price had risen to $8 an ounce.

By this time, there was a legitimate silver shortage. Over forty-three million ounces were purchased through the COMEX and the CBOT, with delivery scheduled to take place that coming fall. This caused the price to double yet again, this time from $8 to $16 an ounce in just two months. The COMEX and CBOT attempted to place new restrictions on the ownership of silver, but the Hunts bought even more, and soon the price had reached an astonishing $34.45 per ounce!

The price of silver continued to climb. On January 17, 1980, it hit $50 an ounce. At that time, the Hunts held $4.5 billion in silver—a $3.5 billion gain on their $1 billion investment. The various limitations and rules changes imposed by the commodities markets had no effect but to push the price of silver higher, until finally the COMEX announced that it was suspending the trading of silver and henceforth would only accept liquidation orders.

Of even greater significance, Paul Volker had been installed as the Chairman of the Federal Reserve, and Volker was determined to get runaway inflation under control. The Chairman abruptly raised interest rates, thus soaking up the excess liquidity which had helped fuel the silver boom. The price of an ounce quickly dropped to $39, and by March 14, it was down to just $21.

Nevertheless, the Hunts could have made billions if they had known when to get out of the market. But alas, as the price of silver fell to $21, the brothers had future contracts obligating them to buy at upwards of $50 per ounce. On March 25, 1980, the Hunts couldn’t make their $135 million margin call, and Bunker phoned his brother Herbert with three ominous words: “Shut it down.”

Is Silver Manipulation Happening Again?

Silver closed at $21.62 per ounce on Wednesday, March 26, 1980. But the following day—the infamous “Silver Thursday”—saw the value of the precious metal decline by more than 50%, closing at just $10.80. The Hunts had assets of $1.5 billion but liabilities of $2.5 billion—making them the greatest debtors in the history of finance (excluding governments, of course). Ultimately, they had to be bailed out by their despised enemies, the New York banking establishment, who issued them $1.1 billion in credit to make good on their obligations.

In 1988, Nelson Bunker Hunt filed personal bankruptcy and was convicted of illegally attempting to corner the market in silver. But don’t shed a tear for Bunker—the trusts set up for him by his father are currently valued at more than $200 million. Bunker exited bankruptcy in 1989, and had satisfied a $90 million debt to the IRS by 2006. Even more so than his commodities-market exploits, he is best known as a owner-breeder of thoroughbred racehorses, for which he has won numerous awards.

The message of the Hunt brothers story is a lack of financial education can be the downfall of any silver investor—even billionaires. In many investors opinion, it is much preferable for investors to hold silver as bullion or, alternatively, through the indirect ownership of silver mutual funds. Although, individual financial education is required for success in any market.

Although it is unlikely that a pair of wealthy brothers could corner the market in silver today, the short ratio of silver is quite high, and upwards of 90% of these short contracts are held by just four traders.

Precious metals are typically held as a hedge against government mismanagement of fiat currency, but the silver market seems poised for yet another dramatic swing.

Pingback: » The Long and Short of Silver – Cabal of Traders Manipulating the Price of Silver?

Pingback: » Bulls vs. Bears: Who Will Win the Silver Battle?

Pingback: » Gold and Silver: The Historical Relationship and What it Means to Today’s Investors